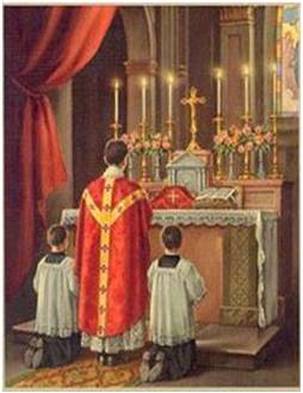

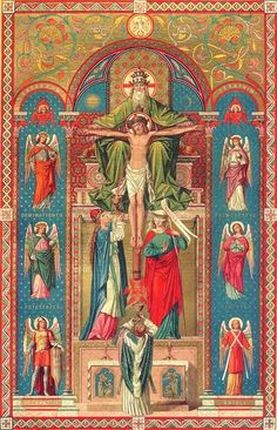

Our priest is turned toward the East (ad orientem). This ancient orientation goes back to the Apostles signifying that the priest is not only praying to God but also that the whole cosmos (i.e. the rising sun in the East) yearns for the return of Jesus Christ who will come again from the East. Breaking the closed circle, the priest orients all of us and our prayers toward God. In the Person of Christ (in Persona Christi), our priest has a great work/service (leitourgia) to perform: Look at him, the priest with his back turned, with his face, his hands, his heart fixed on the mystery of faith--he disappears, to be replaced by Christ; he vanishes, and yet he is more himself than ever. . . . . he is the very agent and medium through which the Lord acts to unite, sanctify, and recapitulate all things in himself. (1) Having commenced the Mass with the prayers at the foot of the altar, the priest moves to the epistle side--the right side of the altar from the people’s perspective (2). Signing himself with the cross he begins to pray the Introit that usually consists of a short antiphon from Scripture, a verse from the Psalms, a Gloria Patri, followed by the antiphon once again. The Introit is the “entrance” of the Mass of the Catechumen in which the Word of God prepares us for the Sacrifice of the Mass. Because the Introit is one of the “propers” of the Mass, it will change to fit the commemoration of the day. This prayer sets the tone for the Mass--rejoicing, mourning, repenting, etc.--instructing us to share in the full experience of the Saints and Jesus Christ himself. For example, for the Feast of the Immaculate Conception we should rejoice because the Son has chosen his Mother: “Rejoicing I will rejoice in the Lord and my soul shall exult in my God, because He has clad me with the garments of salvation, and has surrounded me with the vesture of gladness, like a bride adorned by her jewels.” And the Psalm: “I will extol Thee, O Lord, for Thou hast upheld me: and hast not made my enemies to rejoice over me.” Our dispositions should conform to the seasons and feasts presented to us in the Introit lest we think that this world is our home and that our own emotions should determine our actions and thoughts. For this reason, it is a good practice to be aware of the content of the Introit before Mass. Whatever the particular emphasis of the Introit, awe of God’s holiness and justice should fill us, disposing us to humble ourselves unto contrition. Hence, the Mass swiftly moves from the Introit to the Kyrie in which we beg for God’s mercy. Now at the center of the altar, our priest begs God for His mercy a total of nine times, petitioning each of the Divine Persons three times (Kyrie Eleison). And we beg with him. Such repetitions not only place us in a posture of humility but also emphasize the Trinitarian nature of God in which the Persons are not only distinct but each indwell within in the Other in substantial union. It is also a reminder that the Sacrifice is to be offered to God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. So too the Gloria in Excelsis Deo reinforces the primary purpose of the Mass: Glory to the Trinitarian God. Even our own salvation is subordinated to the glory of God. We give him thanks on account of his great glory (propter magnam gloriam tuam). We are saved so that He might be glorified in His creation. This is a hard but liberating truth. Our priest kisses the altar before turning to the people: Dominus vobiscum. The server: Et cum spiritu tuo. He kisses the altar out of reverence for the Sacrifice that will be offered on this altar shortly. He prays for the presence of the Lord to be with us so that we might be ready for the Sacrifice(Dominus vobiscum), and we pray for him that he might be ready to offer this Sacrifice with clean hands and a pure heart (et cum spiritu tuo). Turning back to the Lord, he returns to his work/service (leitourgia) moving to the epistle side (the right side): Oremus. Oremus: Let us pray. In the Collect, our priest collects the prayers of the faithful offering them to God. We pray with him uniting our prayers with the priest in the form of the feast or saint celebrated. For the Feast of the Blessed Sacrament the Collect reads: “O God, who under a wonderful Sacrament has left us a memorial of Thy Passion, grant us, we beseech thee so to reverence the sacred mysteries of Thy Body and Blood that we may continually find the fruit of Thy Redemption in our souls..” Even our petitions are molded by the commemorations of the Church lest we rely on our own fickle hearts. The epistle taken from the Old or New Testament is read to serve the particular lesson that will come in the Gospel and, consequently, to magnify the works of Christ and the saints commemorated on that particular day. Let us thank God for his holy doctrine which saves: Deo Gratias. Now let us observe the deacon or priest ascend the steps (gradus) while the Gradual is sung echoing the contents of the Introit. Then let us stand for the very words of our Lord signifying our readiness to follow wherever He may lead. St. Alphonsus Liguori also notes that the priest goes to the other side of the altar to signify that the Gospel has been accepted by the faithful while the Jews have refused to hear the Gospel--an exhortation for us to proclaim the Gospel to those who have stopped short in the Old Covenant. Indicating the greatness of the proclamation of the Gospel, the priest prays: “Almighty God who didst with a burning coal purify the lips of the Prophet Isaiah, cleanse also my heart and my lips of Thy merciful kindness vouchsafe to purify me that I may worthily announce Thy holy Gospel through Christ our Lord. Amen.” Then crossing the text--as if to say: “This is the book of the crucified One”--and crossing himself three times (and so do we): “May the Lord be in my heart and on my lips that I may worthily and in a becoming manner announce His Gospel.” The explanation of the Gospel in the homily is the end of the first part of the Mass, the Mass of the Catechumens (Missa Catechumenorum). The unbaptized must leave because their souls are not marked with the common priesthood that is necessary to be present at the Sacrifice to come in the second part of the Mass, the Mass of the Faithful (Missa Fidelium). Notice how the Mass slowly ascends to its center: the Sacrifice. Back to the Altar. Let us rise for the great Symbol of the Faith, the key that opens the door to the Mass of the Faithful: the Nicene Creed. The recitation of the Creed is more than a sign of our intellectual assent; it is a sign of our full trust in the Persons of the Godhead, as the Latin makes clear (Credo in Deum. . . .). In the creed you and I should mean: I thrust my whole existence into God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. Only such a firm resolution makes us worthy to enter into the Holy of Holies of the Altar. St. Alphonsus Liguori exhorts us: “While the priest is reciting the Symbol, we should renew our faith in all the mysteries and all the dogmas that the Church teaches. By the symbol was formerly understood a military sign, a mark by which many recognize one another, and are distinguished from one another: this at present distinguishes believers from unbelievers.” We are ready to enter the Holy of Holies. May we orient our wills and intellects to the fourfold end of the Sacrifice: Adoration, Thanksgiving, Impetration, and Expiation. _________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Kwasniewski, Peter. Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church. Highly recommended! 2. In the 16th century Pope St. Pius V proclaimed that the sides of the altar should be labeled according to the perspective of the crucifix. In other words, the right side of the altar for the people would actually be called the left side, and the left side of the altar would actually be called the right side. In order to avoid confusion, I have labeled them according to the perspective of the people. 3. Much of the material for this post comes from M. Gavin, S.J., The Sacrifice of the Mass: An Explanation of its Doctrines, Rubrics, Prayers https://archive.org/stream/sacrificeofmass00gaviuoft#page/n0/mode/2up  The center of the Mass is the Sacrifice of the Altar: the Holy Eucharist. Before we reflect on the second movement of the Traditional Mass, I think that it would be beneficial for us to pause and reflect on the purpose of this Sacrifice so that we might rightly understand each movement of the Ancient Liturgy. All movements, prayers, and deliberate moments of silence within the Traditional Mass exist for the sake of the Sacrifice. For this reason, our meditations and internal acts of piety throughout every part of the Mass, from the prayers at the foot of the altar to the Last Gospel, should be directed towards this Sacrifice offered to God. But why is this Sacrifice offered to God? In her authoritative Tradition the Church has taught that there are four reasons for which the Sacrifice is offered to God: 1) Adoration, 2) Expiation, 3) Thanksgiving, and 4) Impetration. With the aid of St. Alphonsus Liguori let’s briefly reflect on each one of these reasons for the Offering. First, we offer the Eucharistic Sacrifice to adore and honor God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Because Jesus Christ offered himself in perfect love and obedience to God on the Altar of the Cross, we are now able to offer up what he himself offered, namely, his perfect Body and perfect Blood. Any other offering is an imperfect adoration of God. This is no small point. The history of religion has demonstrated that man is unable to adore God in proportion to His perfect Holiness, perfect Goodness, perfect Justice, etc. Man is incapable of fulfilling his duty of religion if he is incapable of giving God his proper due. All of those bloody sacrifices of the Old Covenant and of the pagans were a vain attempt to offer God his proper due. In other words, man could establish no just act whereby he could acknowledge the Perfection of God. The New Covenant overcomes this severe impotence. Through the Sacrifice of the Altar you and I are able to offer perfect adoration to God. We can finally say that we have a Sacrifice that is “fitting and just” (dignum et justum). We can finally rejoice in the fact that we mortals can fulfill our duty to adore Him. Thus, St. Alphonsus Liguori states: “My God, I adore Thy majesty. I would wish to honor Thee as much as Thou deservest; but what honor can I, a miserable sinner, give thee? I offer Thee the honor which Jesus renders to Thee on this altar.” Second, the Sacrifice of the Eucharist is offered to God for the expiation of our sins. Because the Sacrifice on Calvary is the same Sacrifice that Christ himself offers in the Mass, the priest offers it to God as the complete satisfaction for man’s sins. Because he himself offered perfect love and obedience to God in the separation of his Blood from his Body on the Cross, the Sacrifice of the Altar has infinite value. Even though the Victim and Priest of this Sacrifice has infinite worth and merit, the fruits of this Offering in regards to forgiveness of sins and of temporal punishments for sins are finite because they depend upon the disposition that we bring to the Mass. For this reason our dispositions are of prime importance when attending Mass. Therefore, St. Alphonsus helps us realize the proper disposition in this prayer during the Canon of the Mass: “Lord, I detest above every evil all the offences that I have given Thee: I am sorry for them above all things, and in satisfaction for them I offer Thy Son, who sacrifices himself for us on this altar, and through his merits I pray thee to pardon me, and to give me holy perseverance.” Thirdly, just as man was incapable of offering proper adoration to God before the New Covenant, so was he incapable of giving proper thanksgiving to God. In ourselves we are incapable of offering Him the thanksgiving that he is owed. Because of this inherent impotence in man, it is we that suffer because we cannot do what our souls desire to do: to give perfect thanksgiving to God for who He is and what He has done. Through this Sacrifice alone are we able to offer a proportionate thanksgiving (eucharistia) to God for his Goodness. We can now say with St. Alphonsus: “Lord, I am unable to thank Thee; I offer Thee the blood of Jesus Christ in this Mass, and in all the Masses that are at this moment celebrated throughout the world.” Finally, the Sacrifice is offered up for the sake of petition or impetration. When the Sacrifice of the Mass is offered to God we should make our petitions (impetrationes) made known to Him. It is through his perfect Sacrifice that our spiritual and temporal goods should be brought to the Giver of all good things. Thus from Communion to the end of the Mass St. Alphonsus states: “You will ask with confidence the graces that you need, and particularly sorrow for your sins, the gift of perseverance, and of the divine Love; and you will recommend to God, in a special manner, the persons with whom you live, your relatives, poor sinners, and the souls in purgatory. If we wish to be active participants in the Mass, we should return to these four reasons for the Sacrifice of the Mass. When we forget why we are at Mass we need to remind ourselves that we are here to adore Him, we are here to offer Him thanksgiving, we are here to offer expiation for our sins, we are here to petition Him for His good things. And through the Sacrifice of Jesus Christ made present on the altar, we are able to do all of the above efficaciously. But while reflecting and meditating on the Sacrifice as an Offering to God, we must not forget that it is a Sacrament of Charity and Gift to man whereby the Sacrifice redounds to us in perfect communion with Jesus Christ. For indeed the Eucharist is not only called the Sacrifice; it is also called Communion. |

AuthorsThe authors of this blog are the tutors of Saint John of the Cross Academy: Archives

November 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed