|

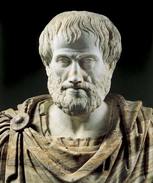

The most common kind of pitfall in rational discourse is fallacious reasoning resulting from the ambiguity of terms, sometimes called “equivocation”. As Aristotle wrote,

Words are often used imprecisely and in many different senses without those senses being clearly distinguished, which leads to false conclusions. This ambiguity was elevated to a profession by those the Greeks called “sophists,” for whom it was more important to appear to reason properly than to actually do so.[2] But even besides those who intentionally make use of ambiguity for their own gain, there are those who through ignorance make use of an fall prey to this fallacious reasoning. Unfortunately, this is the case with many of those in the public eye who have a platform to speak, yet have no no training in dialectical reasoning. With the near total abandonment of the rigorous dialectical methods of the Scholastics, equivocal argumentation is all the more common in our era.

As we have seen, men charged with representing Holy Mother Church are not at all immune to this kind of error, which is especially dangerous because it has the potential of distorting faith. A prime example of this was on display after the October Synod of last year in a statement made by Fr. Thomas Rosica, who was chosen to be the English-language spokesman for both last year’s Synod and the one which is now underway. Here are his words:

Consider Fr. Rosica’s use of the word “irregular” here. In the context of Church law, which is the relevant context when discussing the moral status of sexual relationships, “irregular” means unlawful. That is to say, if a certain person is willfully persisting in an irregular relationship, then that person is in open defiance against the laws of the Church. Willful persistence in an “irregular” relationship in this sense is therefore sinful.

But surely Fr. Rosica would not assert the same sense of the word when applied to the marital status of the Blessed Virgin and her most chaste spouse, Saint Joseph. In the context of Fr. Rosica’s statement, “irregular” is most charitably understood as “abnormal” or “uncommon.” This is, of course, true. The relationship of the Holy Family is certainly uncommon. But if this is all that Rosica means in using the word “irregular,” then his comment is simply irrelevant to the discussion of Church teaching regarding canonically irregular relationships. Though it may be true that canonically irregular situations are also uncommon situations, the sense of irregular cannot be reduced to ‘uncommon,’ since even if everyone in the world was in an irregular situation, it would remain irregular even though it was common. To equivocate here is to reduce canonical irregularity to mere uncommonness, and thereby reduce canon law to a statement of what is common. This is dangerously close to acquiescing to all who say that Church teaching is merely the expression of an outmoded norm which is of no practical use in the modern world. If irregularity is identical with uncommonness, then once a situation became common, it would follow that it should also become regular; that is, lawful. This is the very definition of moral relativism, and is at the heart of heresy of Modernism that has been condemned by the Church. It must be said that Fr. Rosica, for all I know, may be invincibly ignorant in his equivocation. He may simply be a sloppy thinker who speaks without fully understanding the implications of what he is saying. Twitter certainly lends itself to this kind of haphazard and irresponsible expression. There is not necessarily any very grave sin in that. But as a spokesman of this Synod, it is at least incumbent upon him to correct such foolish phrases and pursue clarity over paper-thin phrases that only add to the noise which has crippled true dialogue.

NOTES:

[1] Aristotle, On Sophistical Refutation, 1.1 [2] ibid, Aristotle very interestingly compares the sophist, who seeks only to appear wise with his ambiguous argumentation, to the person who is not beautiful, but only appears so on account of outward embellishments: “That some reasonings are genuine, while others seem to be so but are not, is evident. This happens with arguments, as also elsewhere, through a certain likeness between the genuine and the sham. For physically some people are in a vigorous condition, while others merely seem to be so by blowing and rigging themselves out as the tribesmen do their victims for sacrifice; and some people are beautiful thanks to their beauty, while others seem to be so, by dint of embellishing themselves. … In the same way both reasoning and refutation are sometimes genuine, sometimes not, though inexperience may make them appear so: for inexperienced people obtain only, as it were, a distant view of these things. … Now for some people it is better worth while to seem to be wise, than to be wise without seeming to be (for the art of the sophist is the semblance of wisdom without the reality, and the sophist is one who makes money from an apparent but unreal wisdom); for them, then, it is clearly essential also to seem to accomplish the task of a wise man rather than to accomplish it without seeming to do so.” |

AuthorsThe authors of this blog are the tutors of Saint John of the Cross Academy: Archives

November 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed