|

Back in February, I wrote a letter to my fellow parishioners at Saint Leo IV Roman Catholic Church in Roberts Cove, LA, where I currently serve as Choir Director. The letter was intended to explain why we insist on singing Latin in the Mass. A parent at our recent seminar suggested that I post that letter here for the benefit of the whole SJCA community, so I am now doing so. I hope it serves as at least a good introduction to the necessity of preserving liturgical Latin, something which we take to be particularly important at SJCA. Look for much more to be written here on this issue in the future. Why Latin?

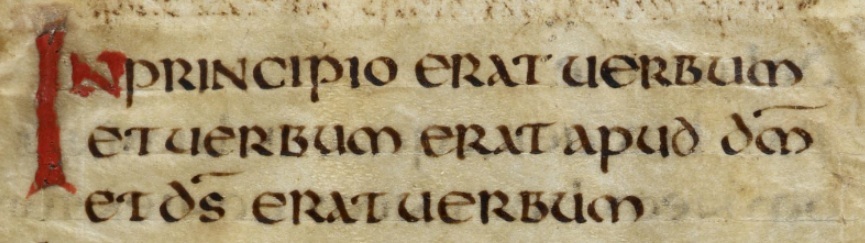

by Peter Youngblood “The Catholic Church has a dignity far surpassing that of every merely human society, for it was founded by Christ the Lord. It is altogether fitting, therefore, that the language it uses should be noble, majestic and non-vernacular.” - Pope Saint John XXIII, Veterum Sapientia (1962) These words from the recently canonized Saint John XXIII, who convened the Second Vatican Council, should help to answer for us why the Roman Catholic Church for so long has doggedly held to its ancient Latin language. This question has been the subject of much debate among Catholics in the decades that followed the Council. It is often asserted that Vatican II made the use of Latin simply optional, or even that it freed the faithful from the “shackles” of this “long-dead” and “unintelligible” tongue completely. My purpose in writing this, as your fellow parishioner, is to try and lend some perspective on this topic and to very briefly defend the continued and frequent use of Latin in the our celebration of the Sacred Liturgy at Saint Leo’s. Let us begin our consideration by making sure we have all the evidence. What did the Second Vatican Council really say about the use of Latin in the Sacred Liturgy? The documents of the Council, much the same as the pope responsible for convening the council, express something very different than the modern assumption. “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 36). That is to say, Latin remains the liturgical and sacred language of the Roman Catholic Church. It may now be asked: “But is it not true that the Council made an allowance for the use of the vernacular in the liturgy?” The answer, of course, is yes. However, we must note the key word here: allowance. As the Council states: But since the use of the mother tongue, whether in the Mass, the administration of the sacraments, or other parts of the liturgy, frequently may be of great advantage to the people, the limits of its employment may be extended. This will apply in the first place to the readings and directives, and to some of the prayers and chants. (ibid, 36.2) What should become clear here is that the Council never intended to replace Latin as the liturgical language of the Church. It remains the language of the Latin Rite of the Church. The limits upon the use the vernacular are merely “extended,” not removed as is often thought. Thus, this allowance actually serves to further emphasize the primacy of Latin in the liturgy rather than rendering it unnecessary. The clear message from the Fathers of the Council is not a demotion of Latin, but a reaffirmed promotion, in line with the intention “to ensure that the ancient and uninterrupted use of Latin be maintained and, where necessary, restored” (Saint John XXIII, Veterum Sapientia). Lest this be thought of as a directive applying mainly to priests and religious, the Council mandates that “steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 54). With all that said, the question remains: Why does the Church insist on Latin? What makes Latin so special as to be preferred above all other languages in the western world for the Roman Catholic Church? In answering these questions, I think it is worthwhile to take a step back and consider what makes any language important. Here in Roberts Cove, I believe this consideration will come naturally. I learned very quickly how special the German language was to you all when I was first given the position of choir director here. I had chosen a hymn that I love, Holy God, We Praise Thy Name, an english rendering of the Te Deum, to sing at my first Mass as director. When I presented my hymn selection to the members of the choir, they quickly shot back that Saint Leo’s doesn’t sing “Holy God,” but always and only “Grosser Gött.” I learned fast, and was very appreciative of the lesson. What the choir members did was quickly jump to the defense of their tradition. And this is commendable. In the hyper-progressive modern world, we must fight to conserve our traditions if we do not want them torn from us, either by force or by our own slothful carelessness. The members of the choir were actively preserving their living connection with those that had come before, those that had founded and cultivated their small and beautiful community. I was happy and will always be happy to help preserve this community however God allows me to. It is precisely this appreciation and preservation of tradition that makes me continually grateful to be here. I relayed this story to make a point about the inextricable connection between culture and language. There is simply no preserving a culture without preserving the language. This is because language is the very veins of culture. It is the living connection between us and our past and the vehicle that transports the life-blood of culture, which is tradition. We hold to the language because it ensures our connection as one people with our ancestors. Now there are many reasons that I could rattle off for the preservation of Latin, from its deep beauty of expression, to its clarity and noble simplicity. But none of those reasons penetrate as deeply into the life of the Church as the reason I am describing now. Latin is the language of the Roman Catholic Church. It is, as it has been for millennia, the language in which our Faith and prayer is expressed. Therefore, to hold to Latin is to hold to the spiritual culture, the patrimony of the Church, just as holding to German is to hold to the patrimony of Roberts Cove. What’s more, the Church’s is no merely human culture and patrimony. It has been baptized in the providential grace of God, by which the Church has always been guided throughout her life on earth. When we pray the Mass in Latin, we are enacting that living connection to the Church Universal, the Saints that have come before us and have gone ahead into blissful union with the Triune God. That makes preserving Latin far more than a merely human and cultural duty. It is a spiritual and sacred duty. Thus, “the use of the Latin language,” Pope Pius XII said, “affords at once an imposing sign of unity and an effective safeguard against the corruption of true doctrine” (Mediator Dei). Latin may well not be a vernacular language in that it is not spoken as a mother tongue by any natural society in our age. But this is fitting, because the Church is no merely natural society, as Saint John XXIII reminds us in our opening quote. It is a society whose head is Jesus Christ, God Incarnate, and whose life is communicated to us through the ministry of the Holy Spirit sent to us from the Almighty Father. Why Latin? Because it is our sacred language as Roman Catholics. And just as it takes great effort to preserve our natural heritage, it takes great effort to preserve our sacred heritage. Pope Saint John Paul II reaffirmed the duty to do so: “The Roman Church has special obligations towards Latin, the splendid language of ancient Rome, and she must manifest them whenever the occasion presents itself” (Dominicae Cenae). It is lamentable that so few of us understand proficiently this sacred language. We are not alone. Latin, especially the sacred version of Latin that has been the liturgical language of the Roman Church, was not a language perfectly understood by many people for the majority of the life of the Church. But this is the rule for sacred languages rather than the exception. Orthodox Jews, for example, still use ancient Hebrew in their sacred rituals, even though the use of Hebrew for any common purpose had ceased hundreds of years before the birth of Christ. This is acceptable because what is being communicated in any sacred language is meant to be a mystery that far outstrips the trappings of our own times. Latin is an essential part of the solemn nature of our celebration. Even if we do not understand every word we hear, we are left to contemplate that what is being done is something set apart, something deeply sacred, a great mystery whereby we are connected to God. The liturgy is itself an expression of the “mystery of Christ” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 2). This is not to say that we should not be worried about understanding what is being done and said. Only that we ought to pray for the disposition, while we work to gain a better understanding of our sacred and universal language, to know that all is being said and done for the glory of God. The priest and the choir may use words we do not all understand, but they are not speaking primarily for us anyway. All is for God, through His Church. The liturgy is a gift to us in that it allows us to fully subject ourselves to the Father in a perfect offering to Him of the Body and Blood of His Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. The lack of understanding of Latin, which is no doubt at times a hindrance to the prayer of some who do not have the benefit of a well-formed understanding of the actions of the Sacred Liturgy, is a real problem that requires a real solution. I hope that we can see now, however, the danger of trying to solve this problem by simply suppressing our sacred language. We risk suppressing by the same act our connection to the living tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, which in turn leaves us open to a loss of the virtues of piety and religion, damaging if not totally destroying our sense of the sacred. Let us seek the solution not, therefore, in suppressing that which we struggle to understand, but rather in increasing our understanding. Let us approach the language of our Church with the docility of students, eager to participate fully in the spiritual culture of the Sacred Liturgy, which “builds up those who are within into a holy temple of the Lord” (ibid, 2). It may be difficult and frustrating. You may wonder if it is really worth it, much like some of our younger parishioners might wonder why they are singing Grosser Gött. One day they will learn that they were singing it, even without understanding, because of who they are and where they come from. Unknowingly, they were participating in something far bigger than themselves. Let us then have the childlike faith to do the same with our spiritual mother tongue, the language of Holy Mother Church. After beginning with a quote from the Holy Father that convened the Second Vatican Council, I leave you with a quote from the one who brought it to its conclusion: The Latin language is assuredly worthy of being defended with great care instead of being scorned; for the Latin Church it is the most abundant source of Christian civilization and the richest treasury of piety… we must not hold in low esteem these traditions of your fathers which were your glory for centuries. (Pope Paul VI, Sacrificium Laudis, 1966) In Caritate et Veritate Christi (In the Love and Truth of Christ), Peter Youngblood |

AuthorsThe authors of this blog are the tutors of Saint John of the Cross Academy: Archives

November 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed